How Korean gochu pepper was introduced to Korea does not seem to fit wholly with the scenario that it must have come via the Portuguese somehow through their contact with Japan.

It seems that the Columbus Exchange Theory becomes somewhat vague explaining the details of how chili peppers came to be cultivated in Korea by Koreans.

Korean gochu genetically, along with Sichuan erijintiao (which Chinese food historians themselves trace from Hunan/Hubei/Shandong northeast region), belong to a distinct East Asian clade from modern genetic studies. Instead of being in the same clade as Mexican jalapano which the Spanish clearly recorded observing the natives eat during their conquest for Mexico, the Sichuan erjintiao and Korean gochu are in their own separate “East Asian” genetic clade. How can this be?

Chinese point out that even Sichuan got the red chili peppers from Shandong to Hu migrants closest to Northeast Asia, that spicy hot is a northern cuisine trait and coastal Chinese fear anything spicy.

After a large naval battle with the Ming Dynasty navy, the Portuguese black ships were trounced soundly. The Portuguese were only allowed a small peninsular outcrop far to the south of China, what became known as Macau. Trade was tightly monitored.

However, Portuguese smugglers could have sneaked into coastal towns and had illegal contact with coastal Chinese. Yet, coastal Chinese that could have acquired a taste of chili peppers first actually fear anything spicy. So then at what point would Portuguese slave traders and smugglers insert peppers into Northeast Asia for Hunan to acquire erjintiao peppers to spread to Sichuan?

If erjintiao peppers came from Northeast Asia into China, what to make of the genetic connection of Korean gochu peppers grouped together in an East Asian genetic clade? History and DNA evidence indicates a spread of the ancestor of gochu and erjintiao from a region closer to Korea then toward inland China.

Japanese point out that chili peppers came either from Portuguese slave traders or from Korea during the Imjinwaeran invasion. Japanese historical documents record stealing “Korai koshaw” or Goryeo (Korea) gochu pepper from Korea, a reversal of what the Columbus theory predicts.

With more historical and genetic facts at hand, the Portuguese corollary theoretically developed from the Columbus Exchange Theory seems to not fit all the overlooked or new facts.

The Columbus Exchange Theory fits Europe quite well, since the exchange of foods is well documented. But modifications to postulate that the Portuguese (since Spanish did not spread peppers despite Columbus bringing them from the New World to Europe first) spread peppers from Europe to all of Asia are predictions before all the facts are observed or new facts are considered.

So, if we discount the Columbus Exchange Theory extended as the Portuguese corollary into all parts of Asia, in particular Korea, we are left with the returning to the original question anew: How did Korean gochu peppers get introduced to Korea if the Capsicum annuum comes from a far away place of origin?

For the first step to continue renewing this inquiry, then how about going back further in time, way back to an evolutionary scale of time, as in millions of years ago. An alternative theory for how capsicum peppers made it to Asia is in order to explain the origin of Korean gochu.

So then, where did Capsicum annuum to which Korean gochu belongs actually originate?

Genetic studies so far place the origin of Capsicum in the South American continent. From the same Solanacae ancestral predecessor that existed in both South America and Asia, whence India got eggplant and South America got capsicum peppers.

Capsicum annuum chili pepper started 6 Ma ago, evolved from a northward spread across the South American continent from present day Bolivia region, according to tracing evolutionary reconstructions of geographical DNA flow models.

Capsicum annuum has spread mainly through Central America/Mexico by birds as seed dispersers. The spread even continued into North America.

Birds were responsible for spreading Capsicum peppers across two huge continents. The capsaicin chemical compound that gives peppers their heat sensation makes a preferential evolutionary fit with birds being the primary seed dispersal agents, since birds are unaffected.

Here is a summary of a 2009 early genetic study by Korean researcher investigating the origin of Capsicum annuum (to which Korean gochu belongs) and how birds spread seeds for human domestication.

South America as a continent is the origin of wild capsicum pepper species. There are almost 30 varieties of Capsicum identified now native to South America and Central America and even North America. But only 5 of those species underwent domestication.

The study makes a nice starting point about domestication of peppers in America, locations of origin, and how peppers spread by animals or mainly birds in wild forms and even humans for domesticated peppers.

This study along with others establish the birthplace of capsicum pepper is in South America. More recent DNA chronology studies calculated that peppers split from eggplants and tomatoes 19.6 million years ago.

As the most recent diverging species, Capsicum annuum evolved in the northwest region of South America and spread into Central America. Yucatan Peninsula seems to be the major location of domestication of Capsicum annuum lines into peppers such as the Mexican jalapeno.

But what is interesting in the report on Dr. Kim’s research is that he found Capsicum annuum has been domesticated independently several different times from the wild bird peppers. Interesting…

The big challenging question now remains as to how Capsicum annuum pepper seeds could have spread into Korea. It seems domesticated seeds are not necessary if the wild form of Capsicum annuum are appealing to humans for rapid domestication. If wild bird peppers could reach Northeast Asia, given enough time, independent domestication by prehistoric Koreans is possible.

Quotes:

• Capsicum annuum is one of five domesticated species of chiles and is notable as one of the primary components, along with maize, of the diet of Mesoamerican peoples.

• However, little has been known regarding the original location of domestication of C. annuum, the number of times it was domesticated, and the genetic diversity present in wild relatives.

• To answer these questions, Dr. Kim and his team examined DNA sequence variation and patterns at three nuclear loci in a broad selection of semiwild and domesticated individuals.

• Dr. Kim et al. found a large amount of diversity in individuals from the Yucatan Peninsula, making this a center of diversity for chiles and possibly a location of C. annuum domestication.

• On the basis of patterns in the sequence data, Dr. Kim et al. hypothesize that chiles were independently domesticated several times from geographically distant wild progenitors by different prehistoric cultures in Mexico, in contrast to maize and beans which appear to have been domesticated only once.

• Less genetic diversification was seen in wild populations of C. annuum from distant locales, perhaps as a result of long-distance seed dispersal by birds and mammals.

Domestication of Capsicum annuum chile pepper provides insights into crop origin and evolution

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

19-JUN-2009

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases … 061909.php

Chiles important reservoirs of genetic diversity important for conserving biodiversity

Without the process of domestication, humans would still be hunters and gatherers, and modern civilization would look very different. Fortunately, for all of us who do not relish the thought of spending our days searching for nuts and berries, early civilizations successfully cultivated many species of animals and plants found in their surroundings. Current studies of the domestication of various species provide a fascinating glimpse into the past.

A recent article by Dr. Seung-Chul Kim and colleagues in the June 2009 issue of the American Journal of Botany explores the domestication of chiles. These hot peppers, found in everything from hot chocolate to salsa, have long played an important role in the diets of Mesoamerican people, possibly since as early as ~8000 B.C.

Capsicum annuum is one of five domesticated species of chiles and is notable as one of the primary components, along with maize, of the diet of Mesoamerican peoples.

However, little has been known regarding the original location of domestication of C. annuum, the number of times it was domesticated, and the genetic diversity present in wild relatives.

To answer these questions, Dr. Kim and his team examined DNA sequence variation and patterns at three nuclear loci in a broad selection of semiwild and domesticated individuals.

Dr. Kim et al. found a large amount of diversity in individuals from the Yucatan Peninsula, making this a center of diversity for chiles and possibly a location of C. annuum domestication.

Previously, the eastern part of central Mexico had been considered to be the primary center of domestication of C. annuum.

On the basis of patterns in the sequence data, Dr. Kim et al. hypothesize that chiles were independently domesticated several times from geographically distant wild progenitors by different prehistoric cultures in Mexico, in contrast to maize and beans which appear to have been domesticated only once.

Geographical separation among cultivated populations was reflected in DNA sequence variation. This separation suggests that seed exchange among farmers from distant locations is not significantly influencing genetic diversity, in contrast to maize and beans seeds, which are traded by farmers across long distances.Less genetic diversification was seen in wild populations of C. annuum from distant locales, perhaps as a result of long-distance seed dispersal by birds and mammals.

Across the three loci studied, Dr. Kim and colleagues found an average reduction in diversity of 10% in domesticated individuals compared with the semiwild individuals. Domesticated chiles in traditional agricultural habits, however, harbor unique gene pools and serve as important reservoirs of genetic diversity important for conserving biodiversity.

This summary of the earlier 2009 paper above tracing the spread of Capiscum annuum peppers by the Korean scientist found that genetic diversity was minimal across wide swaths of pepper seeds spread by birds.

“Less genetic diversification was seen in wild populations of C. annuum from distant locales, perhaps as a result of long-distance seed dispersal by birds and mammals.”

What this indicated was that the seeds were dispersed across far distances, hence the genetic sameness. The spread was not step by step pooled localizations giving such Galapagos-type variations from island region to next island.

Some birds flew long distances, pooping the same seed stock of pepper seeds everywhere through long range dispersal. Wide swaths of peppers showed little genetic variation due to being dispersed far by birds from the same pepper seed stock.

In fact, a new species of Capsicum was even found on the isolated Galapagos Islands. Birds managed to even take and disperse pepper seeds on the distant offshore islands, and likely spread them to the Caribbean Islands.

Chili Peppers — An American Domestication Story

https://www.thoughtco.com/chili-peppers-an-american-domestication-story-170336

Domestication Events

At least two, and perhaps as many as five separate domestication events are thought to have occurred. The most common type of chili today, and likely the earliest domesticated, is Capsicum annuum (the chili pepper), domesticated in Mexico or northern Central America at least 6,000 years ago from the wild bird pepper (C. annuum v. glabriusculum). Its prominence around the world is likely because it was the one that was introduced into Europe in the 16th century AD.

The other forms which may have been independently created are C. chinense (yellow lantern chili, believed to have been domesticated in northern lowland Amazonia), C. pubescens (the tree pepper, in the mid-elevation southern Andes mountains) and C. baccatum (amarillo chili, lowland Bolivia). C. frutescens (piri piri or tabasco chili, from the Caribbean) may be a fifth, although some scholars suggest it is a variety of C. chinense.

The Earliest Evidence of Domestication

There are older archaeological sites which include domesticated chili pepper seeds, such as Guitarrero Cave in Peru and Ocampo Caves in Mexico, ranging in age from 7,000–9,000 years ago. But their stratigraphic contexts are somewhat unclear, and most scholars prefer to use the more conservative date of 6,000 or 6,100 years ago.

A comprehensive examination of the genetic (similarities among the DNA from different types of chilies), paleo-biolinguistic (similar words for chili used in various indigenous languages), ecological (where modern chile plants are found) and archaeological evidence for chile pepper was reported in 2014. Kraft et al. argue that all four lines of evidence suggest that chili pepper was first domesticated in central-east Mexico, near Coxcatlán Cave and the Ocampo Caves.

The following is a 2016 study tracing the spread of all Capsicum species which connects well to the above earlier 2009 study focused on Capsicum annuum. Capsicum annuum diverged far north mainly into Central America.

Phylogenetic relationships, diversification and expansion of chili peppers (Capsicum, Solanaceae)

Carolina Carrizo García, Michael H. J. Barfuss, […], and Friedrich Ehrendorfer

Annals of Botany

July 2016

https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/118/1/35/2196131

HYPOTHESIS ON THE ECO-GEOGRAPHICAL EXPANSION OF CAPSICUM

The evolutionary diversification of most larger clades of neo-tropical land plants has been greatly affected by major geological events during the Late Tertiary (since approx. 23 Ma): the continuous uplifting of the Andes (since the Oligocene/ Miocene), extensive marine introgressions in north-western South America (Pebas system; before and during the Miocene), and the relatively late opening of the Amazon lowlands towards the Atlantic since the Miocene/Pliocene.

In contrast, the current species diversity apparently has originated during the Quaternary (since approx. 2 5 Ma), under the influence of climatic oscillations. In line with these hypotheses, a recent time-calibrated phylogenetic tree of Solanaceae estimated the split between Capsicum and Solanum clades and between Capsicum and Lycianthes at approx. 19 and approx. 13 Ma, respectively, i.e. early to mid Miocene.

By then, the ancestors of Capsicum may have come into existence in the present region of Peru, Ecuador and Colombia (Fig. 7), an area of great importance for Neotropical plant evolution during the Oligocene/Miocene.

This result differs from earlier proposals, which sug- gested Bolivia or a continuous belt from south-eastern Brazil to the Andes as ancestral areas for the origin of Capsicum. Regarding current species diversity in Capsicum, S€arkinen et al. (2013) recovered a period around 1– 3 Ma, i.e. the Quaternary, during which major speciation events may have occurred.

The separation of the Andean clade was dated at approx. 10 Ma, i.e. mid Miocene (approx. 12– 10 Ma), when the Pebas Lake system may have acted as an isolating factor in the divergence between the Andean clade in the northern Andes and the remaining genus, represented today by members of the Caatinga clade, distributed along the northern part of the Guyana Shield and strongly disjunct in central to eastern Brazil (Fig. 7).

Rapid speciation events may have occurred later from east to west, resulting in the origin of several Capsicum clades. Extensive areas have been reconstructed for the common ancestors of the Purple Corolla, Pubescens, Tovarii, Baccatum and Annuum clades, which include northwestern Argentina, Bolivia and Peru (Fig. 7).

Actually, the place of domestication of C. pubescens was hypothesized to be either in mid-elevation regions of Bolivia or in northern Bolivia and southern Peru, whereas southern Bolivia was already suggested as the centre of diversity for C. baccatum.

At least since approx. 6 Ma (early Pliocene), migrations from South America northwards may have increased.

This may have allowed the dispersal and new speciation events of the Andean clade of Capsicum towards Central America, as well as later processes of speciation and/or species dispersal from northern South America.

The latter concerns the more recent evolution of the Annuum clade and particularly its economically most important species, C. annuum, the centre of origin of which is apparently in Mexico.

The anagenetic origin of C. galapagoense after long-distance dispersal to the Galapagos Islands would deserve a particular analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

Eleven well-supported clades (four monotypic) can be recognized in Capsicum (Table 3).

Their stepwise diversification and expansion can be reconstructed in a clockwise direction from western–north-western South America over a gap in the Amazonian lowlands to central and south-eastern Brazil, then back to central and western South America, and finally northwards to Central America (Fig. 7B).

The morphological and genetic distinctness of the Andean clade stands out in Capsicum. Rapid speciation has occurred (and may be still ongoing) in the rest of the genus. This has led to the origin of the high number of currently recognized Capsicum species, grouped into the clades recognized here, that can be characterized by a set of particular features.

The diversification of the genus has culminated in the origin of the Annuum clade, in several regions of Central and South America, which has spread across the continent, due to the weediness and the domestication, as the well-known cultivated chilies.

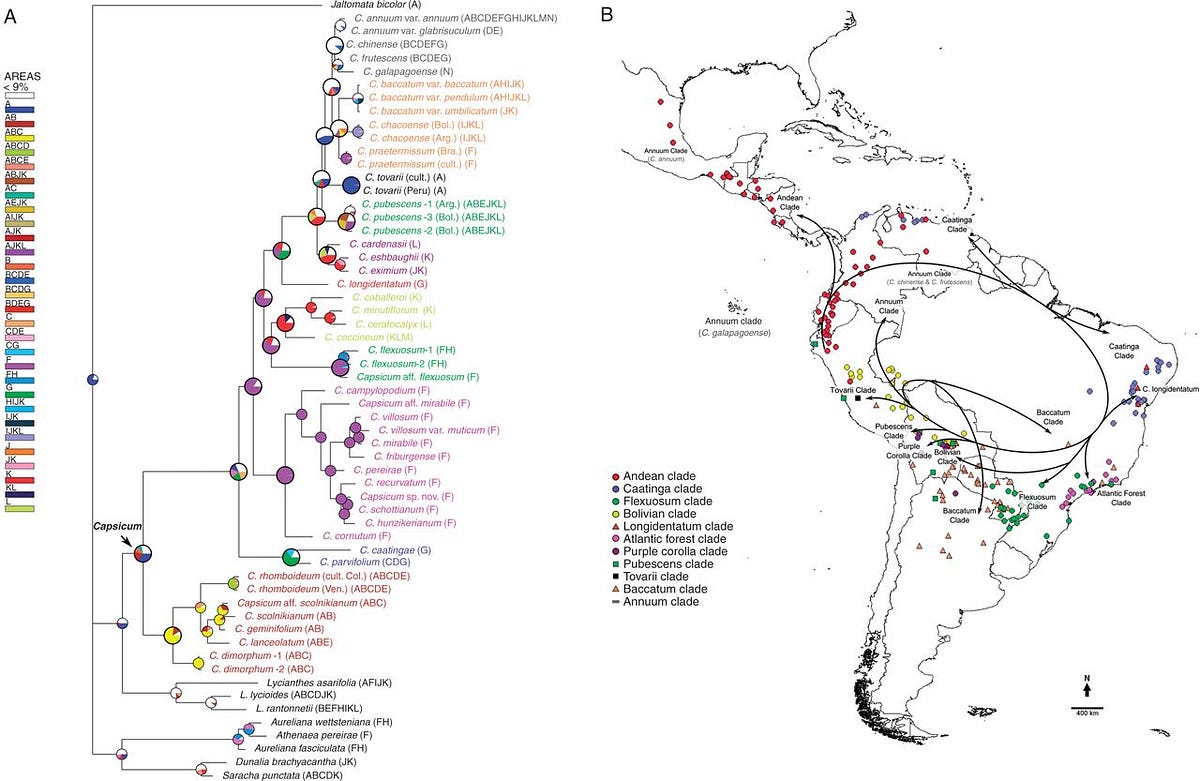

• Figure 7: Hypothesis of Capsicum expansion. (A) Ancestral areas reconstructed by Bayesian MCMC analysis. Pie charts are larger for the main nodes to make them more evident. Area assignment for each species is shown after taxon name. Colour codes reflect the major clades based on the phylogenetic results (grey scale for the Annuum Clade). References: A, Peru; B, Ecuador; C, Colombia; D, Venezuela; E, Central America (including Mexico); F, south-eastern Brazil (Atlantic Forest ecoregion); G, central–eastern Brazil (Caatinga ecoregion); H, north-eastern Argentina and eastern Paraguay (Alto Paraná Atlantic forests ecoregion); I, central–western Paraguay; J, north-western and central Argentina; K, northern, north-eastern and south-eastern Bolivia (mostly lowlands); L, western and south-western Bolivia (mostly highlands); M, western Brazil; and N, Galapagos Islands. (B) Schematic expansion of the species. The arrows represent clades and monotypic lineages going across and/or pointing to the areas inhabited by their species. Markings in different colours/shapes indicate selected population localities. In order not to over-complicate the presentation, the taxa of the Annuum Clade are mentioned in their appropriate place but without markings and partly without arrows.

There does not seem to be any reason to stop the birds as to how far north they could spread seeds millions of years before the last Ice Age.